First, some very important things:

Anyways, back to Tinytroller.

Over the past week, I’ve been intermittently debugging Tinytroller by scoping everything, replacing potentially damaged components, and carefully looking over my board layout and schematic to see where problem spots could exist. And considering ditching the Arduino…

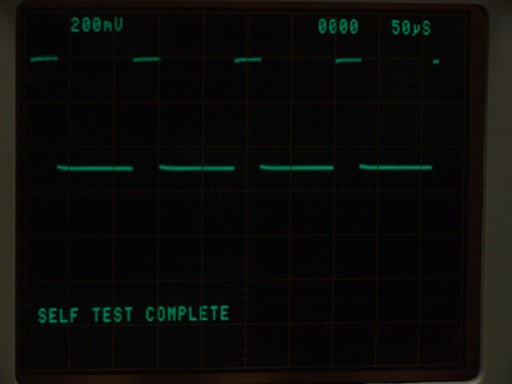

When your gate drive power bus looks like this, you know you’re boned

I’m proud to say that after hours of scoping around and trying various bridging and bypassing and filtering tricks, the problem turned out to be a faulty ground connection which was very high impedance, causing motor switching noise to couple into the logic, causing the microcontroller to crash and reset.

another. software. problem.

Is it any wonder why I hate software?

The problem lay in (of all things) my debugging code, which printed several values (such as the PWM command, motor state, current sensor readings, etc.) over serial. I figured Serial calls on the Arduino just threw your bits and bytes into a buffer and went on. As it turns out, it does, but it will sit there and wait until all said bits and bytes have cleared the buffer, because the buffer is only 1 byte and transmitting ASCII characters takes up far more volume in terms of bytes than transmitting the numerical value of something. All told, with 4 or 5 int values and newlines and tabs being turned into ASCII and transmitted over 38400 baud serial, something like 7 millisconds of loop time was being taken up by the ATmega chip playing with its own serial port.

It turns out that servicing your Hall sensor polls 7+ milliseconds late means the motor has already moved on and you may just be changing states into one which is totally incompatible with the flow of current. This, of course, would drive high voltage and current transients back into the system and cause it to crash or explode.

I am certain that some noise problems may have been eliminated from the original interrupt-driven code version through the splitting of grounds, the addition of fast TVS diodes on the 5v line, and more logic capacitance; but the vast majority of crashing and burning was caused by inadvertent delays introduced through the Serial communication.

Whatever, it works. In fact, it works great. I got Tinytroller running on ported Melontroller code, so it at least puts me back in the black in terms of controller progress – once again, I had an Arduino-powered object that vaguely makes a motor spin. I was able to play with Kitmotter (shown above), and also ran the MITERS Public Etek on a regulated power supply since I didn’t quite trust it on a battery (source of infinity DC amps if needed) yet.

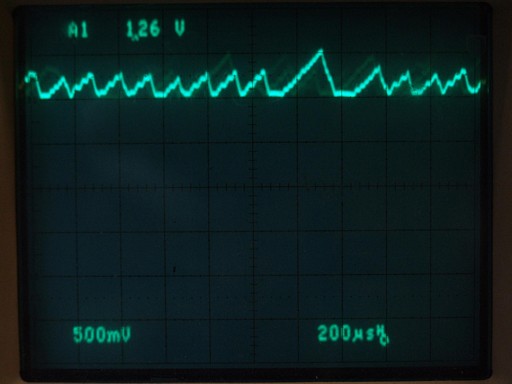

I next put the interrupt-based code back on. And guess what: without those Serial writes blocking traffic, it worked just fine. The interrupt is shown above running at 8kHz and with the pin reads and state table taking up still about 20% of the time. I noticed a small amount of weirdness at low throttle values which made the motor run slightly louder as if it were less well timed, but otherwise did not seem to affect operation or draw obscene currents. Adding various amounts of delay in the ISR (10 to 60 us) caused the “weird period” to move up and down within the range of throttle values. I suspect this may be due to internal events such as the output compare register resetting running into my interrupt service routine…. or some other weird software shit.

Either way, I was unwilling to sacrifice future valuable microseconds in this ISR, so I left it as-is since the weirdness only manifested itself at very low speed.

Without further ado, Tinytroller: The Video!

The scope shot is zoomed in on the ISR, and shows it taking up very small increments of time depending on how far through my state table it had to fall before finding the correct one. However, it seems like 90+% of that time isn’t rummaging through the states at all. Hmmmm….

Regardless, I’m satisfied: If it can hard-brake the Etek from full speed (granted it’s from 25-26 volts only) to zero in under half a second, that’s a pretty stiff introductory transient test.

Next, with Tinytroller having reached the same level of functionality and robustness as melontroller, it’s time to do that thing I said I would never do: write the current-mode controller software. It’s time to add a flywheel to that Etek.