Back in January, I first posted about Deathblades as a distraction from the January build season where I finished Cold Arbor. Since then, it has mostly been a background process. I put the anticipated motor parts in a box and sort of forgot about them for a while.

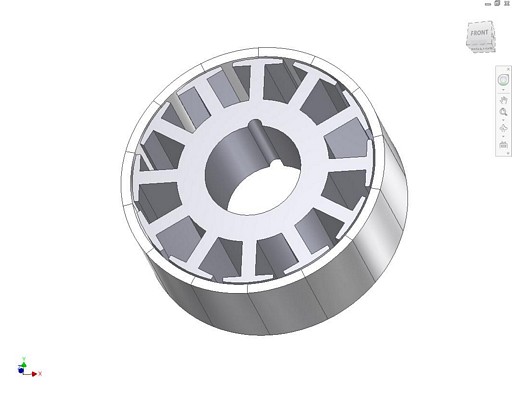

With the semester more than halfway over and the summer build season rapidly approaching, I went back to Deathblades and gave the project a little more thought. Armed with more background on how brushless motors actually worked, I began designing the skate motor around the salvaged copier stators.

Oh, yeah, back in late January, I put together an Instructable on building small hub motors. I’m a fan of intellectual property and product marketing propriety and all, but I also like DIY and individual engineering efforts. So, someone make my work useful and build a hub motor or something.

Let’s start with the basics. This layout is about the same thing I create for every 12 slot motor ever. Since I can have custom magnets made and delivered super-duper cheap, I have elected to skip fudging with flat magnets for now. It’s just not worth the extra effort of making sure they’re all aligned when a full circle only costs a few dollars more.

I elected to keep the usual 0.5mm airgap and design in some 2mm thick 14-pole arc segments.

Altogether, RazEr’s motor is capable of cranking 4 or 5 Nm of torque, and it accelerates pretty well. I want to hit the same target with Deathblades, but since it will have 4 motors sharing that load, it should not be difficult. Average little dLRK motors like this seem to always have a torque constant of 0.2 to 0.3 Nm/A or so, provided you keep the turn count in the mid-double digits.

I discovered through 2.671 that NIBLR overestimates motor torque by about a third just due to the nonidealities that it overlooks. This is fine – I’ll just overspec the motor by 33% or so.

Leap of faith!!

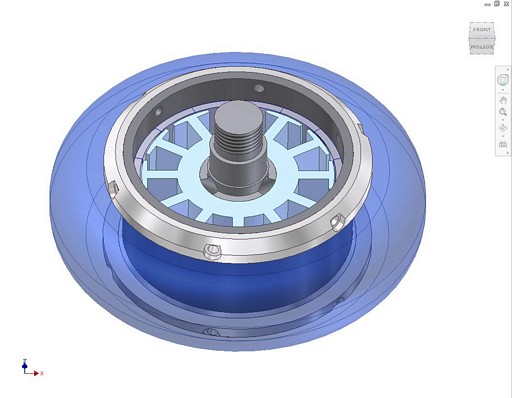

Here’s revision 1 of the design, featuring the dual removable ring structure that I also designed into one variation of the RazEr motor. The wheel is a 100mm skate wheel, specifically from the newest Razor scooters. I chose them after taking dimensions from people around here who owned Razor scooters. They have a rather low tread profile compared to many 100mm skate wheels, which maximizes the motor diameter, and consequently torque.

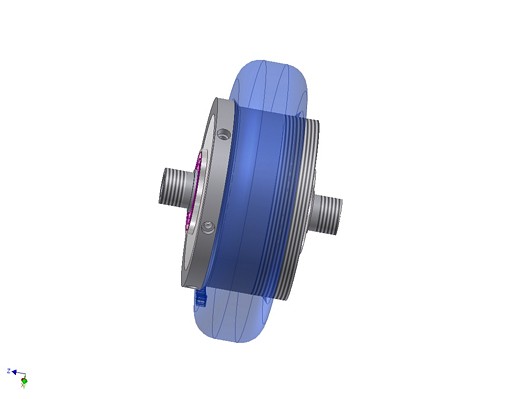

Here’s a cross section of the design that I made for the Instructables page. The skewed hole in the center is for passing wires out of the motor. Otherwise, the lightest blue shade is the stator core, the medium blue is the ring of magnets, and the pink things are type 6902 ball bearings.

Another view of the motor, mostly assembled. I didn’t fill in any windings for this model, but left enough room in the endcap to account for them.

I elected to redesign the motor using the Compromise Solution I used for RazEr. I save on the part count, but the threading is a bit more difficult to pull off right. Hopefully now that I’ve done one, I’ll be better at it.

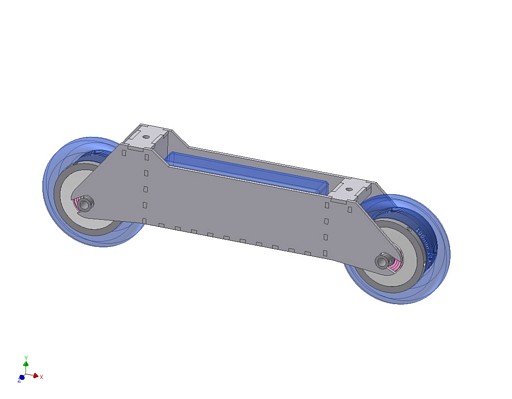

Alright, enough about the motor. I’m satisfied with the motor for now, so I started on frame design. I had stated previously that each Deathblade will probably be two wheeled, as opposed to 4 or more wheels for the average road skate. That’s because I need the central cavity between the wheels for battery and controller volume.

That means I was essentially looking at a box with wheel-mounting flanges sticking out of it, and which has the original Rollerblade boot pattern on top.

The construction will be similar to Cold Arbor’s frame – slotted and tabbed aluminum plate that do not have additional fasteners. I’ll continue using the weird metallic hot glue method that is neither welding nor soldering.

I guess that makes it brazing? Whatever – Deathblade frames will be one-piece for maximum rigidity and strength.

But wait, how the heck am I going to put things in this one-piece chassis?

Well, for one, it will be open at the top. So it’s really a bucket with wheel mounting flanges and the skate’s bolt pattern on it. The above is a rendering of the whole assembly, which can really be strapped to anything – possibly even your arms or hands if you want to skate while doing a constant handstand.

Or perhaps invent some strange variant of street luging.

I kept the wheelbase the same as the original Rollerblade frame’s because I’ve gotten used to their span. That, and I need enough space to fit batteries inside. The blue prism is a geometric representation of a 4AH, 4 cell lithium polymer battery.

So when’s this thing going to be done? Probably not next week or anything, but I want one power unit built by the end of April.